On ‘Understanding Deep Learning Requires Rethinking Generalization’

Published:

Recently, I wrote an essay discussing Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization, one of the Best Paper Award winners at ICLR ’17. This post is an illustrated version of my essay.

The first section of this post introduces some notions of generalization theory and other contextual information for the essay. Readers already familiar with generalization theory can skip this section and move directly to the essay.

Background

In this section, I provide a quick recap of some of the important concepts in generalization theory. For a easy and thorough introduction to generalization theory, I recommend Mostafa Samir’s blog. Prof. Sanjeev Arora’s blog, talk and class are good resources for studying generalization in deep neural networks.

Generalization theory aims at studying the performance of machine learning models on unseen data. The difference between the test error and the train error is formalized into generalization gap, which is defined as the difference between the expected risk, $L_D(h)$ and the empirical risk, $L_{S_m}(h)$. We can prove (for a large set of ML models) that generalization error is bounded above by a quantity that depends on the effective model capacity and the number of training instances. These generalization bounds are of the form

where $N$ is the effective capacity of a model and $m$ is the number of training examples. For instance, for a binary classification problem, we have

where $d$ is the VC dimension of the hypothesis class. Similar generalization bounds can be obtained using other capacity measures like Rademacher complexity as well.

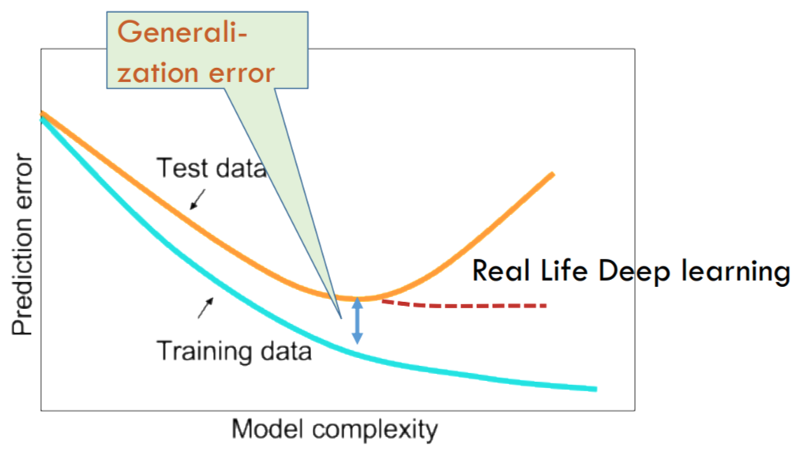

Such bounds explain the typical U-shaped generalization error curve seen with many ML models. However, these bounds are usually vacuous when used with neural networks. Moreover, the same U-shaped curve isn’t observed in the case of neural networks. As the number of parameters of the neural network increases, the generalization error decreases quickly and then either decreases very slowly or saturate. The change is usually accompanied by a minor bump in the curve. Seemingly, the additional parameters aren’t increasing the effective model capacity of neural networks.

The conventional understanding is that the hypothesis space of neural networks is actually much smaller. SGD alongwith regularizers constrict the hypothesis space, decreasing the neural net’s representational capacity, thus keeping the effective capacity small. This isn’t a contradiction to the Universal Approximation Theorem as it merely states that any (real, continuous) function can be approximated by neural network, but doesn’t provide a way to learn the weights.

Essay

‘Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization’ seeks to answer the simple but profound question: Why do deep neural networks generalize? As deep learning practitioners, we know that it’s often a non-trivial task to completely overfit deep networks to real data. The typical U-shaped generalization error v/s model complexity curve we see with traditional ML models isn’t quite observed in deep learning. The conventional understanding is that when deep neural networks are optimized using SGD, their excess representational capacity is destroyed in some fashion to ensure a low effective model complexity. This myth is debunked with the randomization tests described in the paper.

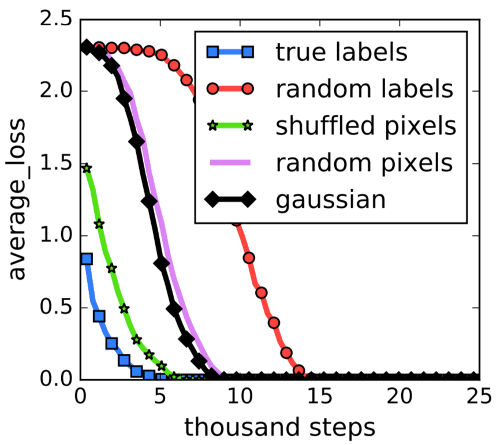

The authors show that deep networks are able to perfectly fit randomly assigned labels to real data, resulting in trained networks that don’t generalize. This experiment shows that SGD by itself doesn’t constrain the representational capacity of deep networks. Surprisingly, the nature of the training process (optimization) is very similar to the case when true labels are used and the training time increases only by a factor of 2–3.

Given that deep neural networks have sufficient representational capacity, why is it that neural nets are able to learn “good” solutions that generalize well. One hypothesis is that explicit regularizers and/or implicit regularizers push the SGD optimization towards these good solutions. Indeed, we all know that explicit regularizers like weight decay and dropout can help in achieving a better test performance. But, we also know that we achieve good generalization even without these explicit regularizations. Hence, explicit regularizers can’t be the fundamental reason why deep neural networks generalize. This is exactly what the authors confirm through their experiments. Further, they also show that often improving the model architecture is enough to get a better generalization performance than adding these regularizers.

However, the process of choosing a particular model architecture and its subsequent optimization involves the implicit addition of regularizers as well. The presence of batch normalization in the architecture and early stopping are examples for such implicit regularizations. Again, much like explicit regularizers, the authors confirm through their ablation studies that implicit regularizations marginally improve generalization performance, but are unlikely to be the fundamental cause for generalization in deep neural nets.

The authors conclude the paper by showing that generalization is perplexing not only in deep neural networks but in other over-parameterized models (number of parameters > number of training examples) as well. Even with the simplest case of linear models, understanding the source of generalization in the over-parametrized regime is difficult.

Thus, ‘Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization’ broadens our understanding of generalization in deep neural networks and opens avenues for future research. The randomization tests raise questions pertaining to the measurement of the effective capacity of neural networks. Traditional complexity measures like VC dimension/Rademacher complexity may not be helpful to prove generalization bounds for deep neural nets and a new measure needs to be sought. Further, this measure of effective capacity should be large for a network trained with random labels and should be low when the network trained with actual labels. As such, this paper allows us to make huge strides in the pursuit of proving generalization in deep neural networks.